So this past weekend was

pernil weekend.

Prep started on Friday, when Dave came home with this hunka burnin' love:

20 lbs of bone-in, skin-on pork shoulder. He had to place a special order at

Gartners Meats, a fantastic butcher shop here in Portland. They, in turn, got it from

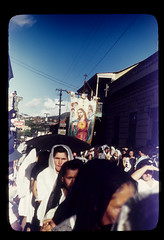

Carlton Farms, purveyor of healthy, rosy pigs to good restaurants all over Oregon. Our particular cut was gorgeous -- this pig led a good life. I ensured a good cooking session for Piggy here by surrounding him with the saints you see in the votive candles.

With the pig finally obtained, we turned to the seasoning. Pork shoulder can be a fairly bland-tasting cut on its own, so it needs some help. When it's 20 lbs, it needs some serious help.

We decided to use a two-pronged approach: stuff it with

sofrito (left)

, and cover it with

adobo (right). I have to confess that the sofrito looks less than stellar because I had made it previously, frozen it for later use, and re-heated it. It tasted good; not great, as with fresh sofrito, but I'll be damned if I'll make fresh sofrito every time I need some. (Recipes at the end of this post).

We started by stabbing holes into Piggy with a steak knife. These holes don't need to go all the way down to the bone, but should be a couple of inches deep. Into these holes you'll be stuffing your seasoning. I just used both ends of a spoon: the spoon itself to start puring the sofrito in, and the handle to gently tamp it down to make room for more. Eventually, you'll start to see it spill out from the hold, and that's when I stuck a slice of garlic in there. You are supposed to stuff it in there until you can't see it, but I left mine peeking out of the holes, so that I could keep track of which ones were filled already. As for the seasoning, sofrito was nice, but I think I'd like to use adobo next time because the flavor is more intense. The bottle of Tecate in the background is not part of the recipe, it's just there for the chef's enjoyment. The cell phone is there for the chef to call her mother and her friend, Elsie, back in PR, for last-minute questions. They've done this before, I haven't.

After stabbing and filling all sides:

our pig is ready to have his garlic secured and be massaged with adobo:

At this point, I placed Piggy in a roasting pan, covered it in plastic wrap, and refrigerated overnight. This bad boy needs time to marinate.

At 5:30 the next morning, we placed it in a 250 degree oven, tented it with foil, and stuck a thermometer in it. (Note: we put Piggy on a roasting rack, and in a roasting pan. For the love of God, don't forget to line the roasting pan with foil, like I did. Unless you like cleaning up a lot of fat, then by all means, forget.) The aim was to cook it low and slow, especially during the hours of 5:30 and 8:15 am, during which both chefs had gone back to bed and did not wish to run the risk of leaving a hotter oven unattended. The temperature was brought up, over time, to 350, then 370, and this cooking process went on for about 9 hours. The smell that permeated the house was unbelievable. Our landlord was outside doing yardwork, and he said he was drooling from the smell. Drooling in a good way.

Nine hours is a crazy-long time, but there's a reason. Bone-in pork shoulder is very fatty. That fat has to render, or else you'll be left with a thick slab of blubber and dry meat. To render this fat and have it permeate the meat and leave it soft, moist, succulent, and a host of other words that I find gross but are really what you're looking for in the end result, the cooking should be done at medium temperatures for a long time.

Once out friend reaches 140 degrees, we can untent it. Also, we can quickly remove it from the oven and pour out the juices, as these will make the inside of the oven humid and prevent the skin from crisping up. I'm told you can make gravy out of the brown bits and juices, but to be honest the juices were very very fatty, and I just couldn't see myself successfully making gravy out of it. If you're thinking you might want to give it a shot, then lining the pan in foil is not a good idea. But really, I'm telling you, it is.

At 180 degrees Piggy is done cooking, and we're ready to make some cracklin' out of that skin. I mean, that's the reason we got it skin-on, so we could make some awesome

chicharrón, or pork rind,

out of it. We blasted it up to 425 degrees for, say 10 minutes. The skin ends up rock-hard to the touch, but once you let the pernil rest you will see that the skin peels off easily. The adobo will have browned and hardened up in clumps, there will be a thin layer of flavorful fat underneath, and I promise you, you'll never have so easily looked heart disease in the eye and said, "Bring it on. Nothing matters now".

I'd like to say that I have a picture of the end result, before it was carved up and eaten. See, what happened was that we were in a hurry to leave, so we packed Piggy up and took it to a potluck. I figured I'd take a picture once we arrived. Well, we arrived, set Piggy down, and went to say hi to our friends. I then grabbed my camera and sauntered back to the table to find this:

You can get a bit of an idea of what the skin looks like from looking at the bone sticking out on the left. Dark, and looking like tanned hide. The picture is blurry because people were waiting to continue picking at Piggy and I had to be fast. You can see the slices of garlic that I stuck in there, and also the sofrito.

This thing was other-worldly. Everybody at the party went crazy over the pernil. I was a bit concerned, thinking that the fatty meat and fatty skin might turn some people off in its primitive, caveman appearance -- especially since Portlanders have a reputation for healthy living. But these people got in touch with their inner primeval hunter and chowed down. The meat was tender enough that slicing wasn't necessary, you could just pull it off with a fork. And if you were lucky, you'd geta piece that was speared with the sofrito and garlic. The combination of the soft-but-present seasoning in the meat was wonderfully countered with the intense saltiness and crunch of the skin. We received many compliments on Piggy. And we learned that while pernil is certainly something that takes time and effort, it's not difficult, and the results it yields are absolutely worth it. Especially that skin and meat mix -- that combo will make you wonder why anyone would want to be vegetarian. Not that there's anything wrong with that, it's just that I couldn't do it. I would think of Piggy, and weep.

AdoboDave came up with the adobo recipe, which is why the measurements are precise.

36 cloves (half mashed up into a paste for the adobo in a mortar and pestle, the other half sliced to stick into the holes)

6 tbsp salt

6 tsp olive oil

6 tbsp vinegar (white or red wine will work)

3 tbsp ground pepper

4 tbsb oregano

SofritoI came up with the sofrito recipe, which is why the measurements are not precise.

2 bunches of cilantro

1 bunch of parsley

3 garlic cloves (or so)

1 red pepper

1 medium onion (or thereabouts)

This gets blended in a food processor until it becomes a paste, or as close as this will get to a paste. This recipe is for a big batch -- I then freeze it in ice cube trays to make it easier to use the sofrito once it's been frozen. For Piggy, I went through about 9 ice cubes of sofrito. I never add salt to my sofrito because I like to control the amount of salt I use right when I am cooking. For the sofrito I added to Piggy, I actually added

a lot of salt. That's as close a measurement as I have, but for this application I would say add as much as you are comfortable with, then add more.

Sofrito's ingredients are usually a bit more interesting that this one's, but they are not easily found around here which is why I substitute. For example, usually instead of cilantro, which is the base,

culantro is used. Culantro is a flat-leafed relative of cilantro and has a headier cilantro taste but with less of an edge. Its flavor profile is too strong to be eaten raw, like cilantro can be, so it is used mainly for cooking. Red and green peppers can be used, but a better flavor comes from

ají dulce, or sweet peppers. I've never seen those here either. I guess it's time to start my own little garden.